|

Sally Winkler Toxic mentorship can thrive in academia, but is often hard to spot. Entrenched power dynamics and internalized imposter syndrome can make victims of toxic mentorship, and their advocates, question if things really are that bad. The list below, while not comprehensive, details a few traits of toxic mentorship. My goal is to identify behaviors to watch for so that trainees can spot toxic mentorship before joining a lab. It may also make it easier for student advocates, including faculty, to identify and support students facing toxic mentorship.

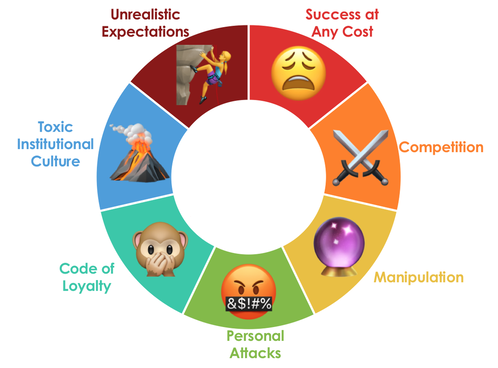

Unrealistic expectations Toxic mentors often set intentionally unrealistic expectations of data quantity or quality so that when the trainee inevitably fails to meet them, the trainee will work even harder to meet the goal. This kind of intense pressure can lead to bad science, especially when a toxic mentor is unwilling to consider alternate hypotheses, despite what a trainee’s data may show. Personal attacks Science is hard and frustration is common. But when critique of a dataset turns to personal attacks against a trainee, this is toxic behavior (“I knew you weren’t good enough to do this work,” “Students who really care come in every Sunday”). Feedback should be free from personal attacks. Competition Many aspects of science are competitive, like funding, publishing, and hiring. But when mentors bring this strong sense of competition into their labs, this can be extremely toxic for trainees. Lab members may race to achieve the same goal, compare hours worked or experiments completed, or fight for limited resources. In a healthy lab culture, mentors encourage collaboration and support among team members. Code of Loyalty Many toxic mentors are deeply invested in lab members being “loyal” to the lab or to the PI (principal investigator). They may use “harming the lab’s reputation” or “spreading rumors” as reasons why it is not appropriate for struggling students to seek input or support from other faculty. This is preposterous; asking for outside help is a normal part scientists’ training, and good mentors know and encourage this. When anonymous criticism does arise (negative tenure letters, ombudsperson mediations, department interventions), PIs may intimidate students to reveal the complainant or stop trainees from speaking up in the future. This is the dark side of a “This lab is a family” attitude; you may tolerate many behaviors from your family that you should not have to accept in the workplace. Success at any cost It may seem like a PI with a strong track record of funding, publications, or institutional support couldn’t possibly be a toxic mentor, and potential advocates sometimes minimize students’ experiences as overblown or unbelievable. Academia, however, does not usually reward healthy mentorship. Well-regarded PIs can still be toxic, and their influence can follow students throughout their careers, especially if the PI is conventionally successful. In some fields, there are “leaders” whose toxic mentorship is an open secret; trainees and faculty peers alike tolerate this behavior because they think “Oh, it’s worth it to have X’s name on your resume.” Communities should seek to give opportunities (speaker invites, awards, etc.) to faculty who treat their trainees appropriately. Manipulation Toxic mentors must be doing something to continue to attract trainees to their group, get money, maintain collaborations, and publish. Often that thing is manipulation. This can take many forms, including high praise and big promises for prospective group members and first year students, while harshly criticizing or totally ignoring older trainees. Harder-to-spot red flags include weird attitudes about data sharing (like keeping data secret from other group members or collaborators) and funny business around money (like how it’s spent or if/when trainees will be paid). Toxic institutional culture In many communities, there is a sense that being treated terribly is par for the course for students and postdocs. That this behavior, which can resemble hazing, is a necessary part of becoming a “real scientist.” Even if many professors in your department/institution behave toxically, or if a mentor doesn’t seem “as bad” as someone else, that does not make it okay. Often, trainees in these toxic cultures will eventually adopt this same mentality, judging newer lab members by these same toxic standards and perpetuating the cycle. Faced with a bad overall culture, ask yourself, “Would this person have been fired if they worked at a company with good HR?” If yes, it’s toxic. Dealing with a toxic mentor can be extremely draining and isolating for trainees. In the best-case scenario, a new trainee would identify toxic mentorship and choose another lab to join. Often, this is not possible, so support from peers and other faculty is crucial to trainees’ success and wellbeing. If you suspect a trainee may be dealing with a toxic mentor, reach out to them and offer to help however you can. Believe them. Trainees in toxic situations, it is not your fault. Ask for support from peers or other faculty and try to find sources of happiness outside the lab. Training scientists well is a crucial part of being a professor, and we should all seek to promote healthy mentorship practices and reward good mentors. About the author: Sally recently completed her PhD in Bioengineering at UC Berkeley and feels compelled to mention that she did *not* have a toxic advisor, which is why she can speak freely on this topic. Many victims of toxic mentorship cannot speak freely about their experiences. It is important for everyone to be informed on these issues so we can collectively support students!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed