|

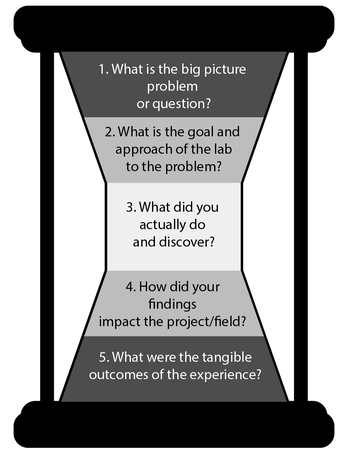

Kayla Wolf As the leaves begin to change color, cool breezes replace summer heat, and Trader Joe's exchanges their normal inventory for nothing but pumpkin themed food, it becomes clear. Application season is in the air. Whether it's a for a fellowship, graduate school, or funding for a virtual conference, now is the perfect time of year to cozy up on the couch and write multiple pages about your life's dreams and achievements. Even amidst the chaos that is our world, at least there are still some intact deadlines to construct a sense of normalcy. Having read >200 application essays as a member of the graduate student admissions committee for my PhD program, a teaching assistant for fellowship-seeking graduate students, and a peer mentor in writing workshops, I have observed some common pitfalls that students encounter when preparing their personal and research statements. Save yourself (and your mentors!) some time now by avoiding these common mistakes. 1. Telling instead of showing In my experience, "telling" instead of "showing" is the most common pitfall as well as the most important to avoid. Telling instead of showing occurs when a student explicitly states how they generally think, feel, or behave instead of showing these abstract concepts through concrete examples of their work. For example, students often write that they "love science" or "work hard." However, saying "I am a hard worker" isn't really convincing. If I am the reviewer, how do I know that the student is actually a hard worker? How do I know that the student and I have a similar idea of what it means to work hard? Showing the committee that you work hard by relaying concrete examples of your work is much more effective. Imagine a student instead writes, "I developed a month-long synthesis protocol, tested the protocol in triplicate, and then assessed the purity using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR)." This student clearly worked hard to develop the protocol and test it three times. This student has also efficiently communicated that they are skilled in basic organic synthesis and NRM without having to list these specific skills and the reader has learned about the student's unique work. Showing instead of telling increases the credibility, word efficiency, and interest of the work. Note the showing should include specific details. These details paint a story in the reader's mind, helping them to understand and remember you. Names of your faculty mentors, the company at which you worked, a specific instrument you used extensively, or an organization where you volunteered are all details that are appropriate to include. Instead of saying you performed "experiments and assays," say "western blotting and qPCR." Instead of saying that you earned a scholarship, say that you earned the "Exceptional Student Award, which is given to one student at the University of the State per year for high academic achievement." Another subtle form of telling instead of showing is what I refer to as a "reflective sentence". A reflective sentence is when students relay their personal thoughts or feelings about an experience retrospectively. For example, a student might write, "I learned how much I love science through this internship and decided I wanted to study biochemistry and go to graduate school." Students often include these as conclusion sentences. Note: not every paragraph needs a conclusion sentence. In addition, a few (1-3) of these reflective sentences throughout the entire essay is more than enough to assure the committee that you love your work. These take up space, are a bit cliché, and can easily derail into a personal monologue. Use them sparingly. 2. Research experience lacks appropriate scope A close second for the most common pitfall is the failure to fully communicate key aspects of a research experience. Internships, research assistantships in a university lab, and intensive class projects that require primary research can all be considered as research experiences. Note that most class projects do not recapitulate the firsthand experience of being in a lab or company, so these should only be included if it is your only experience or your project had an exceptional outcome beyond the classroom. How you frame a research experience is not just a list of bullet points from a resume converted to paragraph form; it is a window for the committee to see how you think as a scientist. Students often fail to explain the big picture (why is the study important enough to do), what their specific role was in the work (as opposed to the work of mentors and the lab), or the outcomes of the experience (whether the work led to a poster, publication, new protocol, a new direction in the lab, etc.). Each experience should described in 1-2 paragraphs or more depending on the number of experiences or breadth of one experience. If you worked in one laboratory for four years, for example, you can break down individual projects as different experiences. The description of the experience should be broad in scope at the beginning, answering why the problem is important to study. Think, "this disease is deadly" or "this organism has unique properties." Next, describe the larger goal or approach of the lab. If the big picture is a need for renewable energy, perhaps the lab is developing new solar cell materials. Importantly, you should identify what work you actually did, such as testing the efficiency of the new solar material described earlier. Finally, you should connect how your work led to progress toward the previously identified goal and list any outcomes. Outcomes can include presentations, reports, publications, a new method or protocol, or any new direction that the lab will take because of the work. With the exception of using 2-4 sentences to describe your work, all other questions can be answered in 1-2 sentences. This change in scope from big picture to narrow to big again resembles an hourglass as shown below. 3. Personal statement is too personal The personal statement is deceptively named, and students often are not sure what should actually be included. Instead of thinking of it as a personal essay, think of it as a "professional-personal" essay. Do not include your life's story. Rather, experiences that were a part of or significantly impacted your career and are unique to you (that's the personal part) should be included. Importantly, the personal essay is a chance to convince the reviewing committee that you will be a good return on their investment. You can also use this space to showcase attributes that are difficult to discuss elsewhere in your application such as teaching experience or volunteer work. What should/can go in a personal essay

What should not be in your personal essay:

4. Informal writing for a formal occasion This one is pretty simple conceptually, but it's easy to forget. Again, while it may be called a personal statement, this is really a professional declaration of your accomplishments with a persuasive element to convince the committee to invest in you. Unlike if you are writing a text to your best friend or a note to your mom, you should follow formal writing conventions in your essays. This means proper grammar, defined abbreviations, a professional tone, and my personal pet peeve, no contractions! Pick up a book on formal writing conventions and have some colleagues take a look at your essays if you need help. 5. Negativity Unnecessary negativity sometimes occurs when a student is trying to communicate challenges they have overcome, particularly when those challenges were other people. It is not appropriate to complain about other individuals or groups of people, including your family and hometown. Students may also use negativity inadvertently to emphasize a positive point. In an attempt to show that they are truly motivated to pursue higher education, for example, they may simultaneously suggest that their community of origin is uneducated, dispassionate, aimless, etc. There is no need to put another scientist, institution, family member, or people group down to build your essay. There is plenty of credit to go around! Happy writing! If you are putting together applications for the first time, check out our podcast on how to ask for letters of recommendation as well.

0 Comments

|

Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed